Ecology of the crucian carp

The occurrence of the crucian carp is linked to stagnant and gently flowing waters with muddy bottoms and dense vegetation. Its original habitat is the floodplains of the lower reaches of rivers. It occurs naturally most often with the sunbleak (Leucaspius delineatus), the weatherfish (Misgurnus fossilis), the common rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus) or the tench (Tinca tinca), but also with other species of fish.

In favourable environments without extensive periods of oxygen depletion, where multiple species are present in the fish community, it tends to be represented by only a small number of large individuals. Conversely, in waters where oxygen depletion occurs, the crucian carp is often the only species present, forming very large populations dominated by individuals up to 10 cm in length. These individuals have a large head in proportion to their body size and are shallow-bodied. In older literature, this form is referred to as the stunted form (Carassius carassius f. humilis). The density of these populations can reach more than 320 kg ha-1. These forms are freely interchangeable depending on the environment in which they occur.

The crucian carps are not very competitive and are not very abundant in areas with large numbers of predators and other competing fish species. Nevertheless, it has developed several adaptations to resist predation and competition. The first strategy is to adapt to an environment in which predators are unable to exist. It is one of the few fish able to survive in small, seasonally anoxic (oxygen-free) ponds. It tolerates low oxygen concentrations through a process called anaerobic glycolysis, where the organism derives energy from glycogen without access to oxygen. This helps it to survive, especially in northern areas where its habitats are covered in ice for several months. Only a few species of fish (such as the striped stickleback) and some species of aquatic turtles can cope with such environments. Predatory fish cannot survive periods without oxygen, and therefore, even if they enter the pool with floodwater, they will not persist permanently. Predation pressure at these sites is therefore only represented by non-fish predators such as kingfishers or herons.

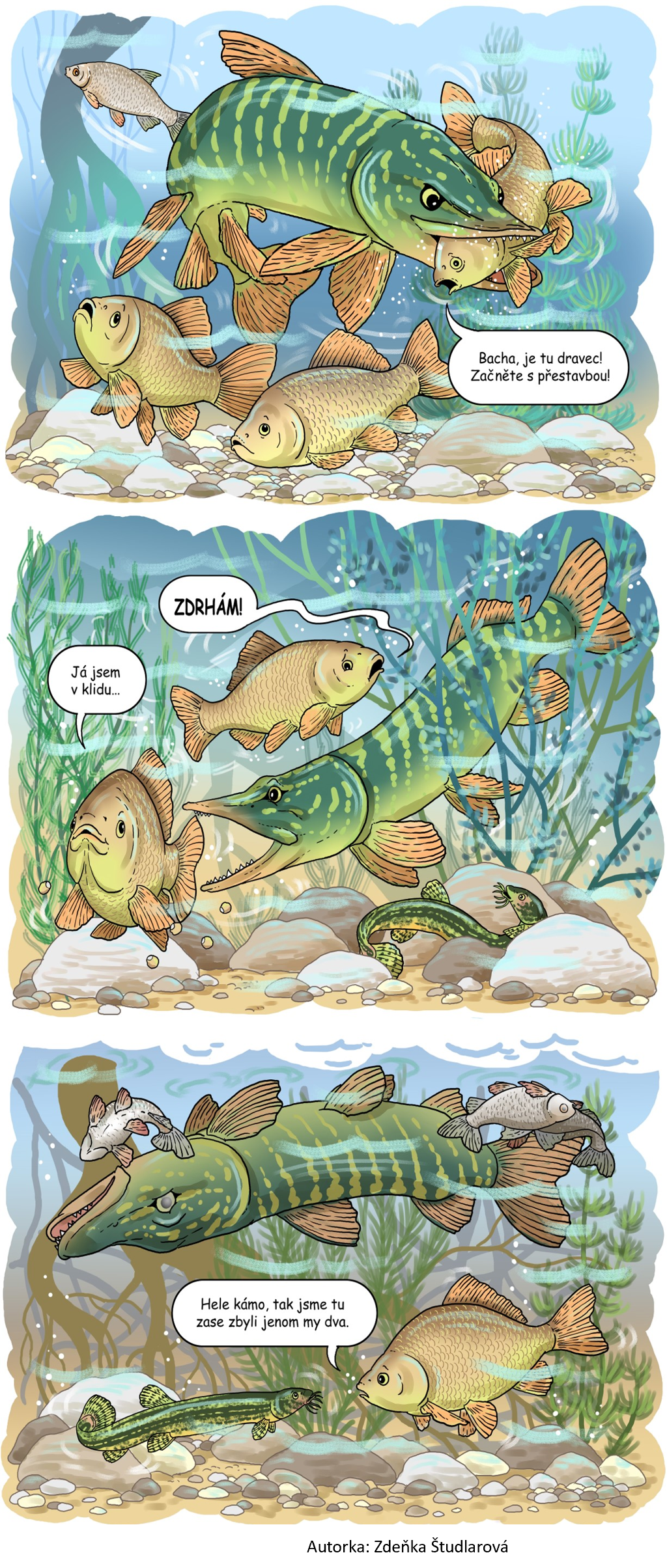

The second adaptation against predators is the creation of a deep-bodied form. If the crucian carp is found in a location where predatory fish species are present, they will develop a deep-bodied form as a defence against attack and their populations consist of a small number of large individuals (1-25 individuals/ha). This deep body size makes it an unavailable food for most sizes of predatory fish species. In addition, it is capable of high escape velocities when encountering a predator such as a pike.

How does the crucian carp know there is a predator in the area?

In environments overgrown with aquatic plants or with low transparency, fish must engage senses other than sight or information from the sideline. In these situations, fish make extensive use of their sense of smell. They have evolved special adaptations for early warning of approaching danger.

If a pike attacks a school of crucian carps and catches one of them, a warning signal is scattered around the area from its wound. The remaining fish avoid the area. Once in the danger zone, the fish keep smaller distances between them and move more cautiously, increasing the likelihood of escape.

Deep-bodied forms of the crucian carp have also been achieved experimentally in laboratory conditions, where researchers have added substances from fish skin to aquariums and observed how the fish react to their presence. The mere presence of the substances triggered a morphological transformation of the body, while the control group kept on the same food and quantity did not show adaptation.

Secondary habitats

The crucian carp has found a second home in ponds and various secondary water bodies. However, in a pond environment, the crucian carp find it difficult to compete for food with the faster growing common carps. It has lost one of its main advantages, its high resistance to environmental stress factors, which cannot be exploited in a managed pond environment. Moreover, in managed ponds, where predatory fish are usually present, the crucian carp is exposed to higher predation pressure, to which they are more susceptible than most other similar omnivorous species. Due to the climate change, periods of long ice and snow cover, which would help to eliminate its competitors, are shorter and less frequent.

Food and reproductive requirements

The crucian carp is an omnivorous fish. It is a so-called benthophage, i.e. a species that feeds mainly on small invertebrates from the bottom. It prefers molluscs, chironomid larvae and other bottom-dwelling animals. However, zooplankton may also form a significant part of the diet. It uses algae and aquatic plants minimally as food because it cannot digest them efficiently.

The crucian carp is a phytophilic species that spawns on aquatic plants. It is spawned in three to five batches during a single spawning period, known as a portioned spawning. It naturally spawns between May and June with an optimum water temperature between 18 °C and 22 °C. It reaches sexual maturity between 2 and 3 years of age. The ratio of females to males is balanced in the population. Both sexes spawn for the first time, usually in the second year of life. Large spawners have up to 300 000 eggs. Growth is relatively slow, highly influenced by the environment and population density. It lives up to 8 years or more.

Phylogeography of the crucian carp or distribution after the ice age

In Europe, genetic analyses have identified two lines of the crucian carp. One lineage (Nordic) is widespread in northern and eastern Europe. In the Czech Republic, this lineage includes the Elbe and Odra river basins. The other lineage (Danube) is found throughout Europe only in the Danube basin. This suggests that a long-lasting barrier remained between the lineages in their geographical areas It is estimated that the two lineages were isolated from each other for 2.16 million years, which corresponds roughly to the beginning of the Pleistocene. Although the Danube basin was an important source for the re-dispersal of freshwater fishes into northern Europe during the glacial period, as is the case, for example, with the European bullhead (Cottus gobio), the European perch (Perca fluviatilis), the European brook lamprey (Lampetra planeri), the European grayling (Thymallus thymallus), the common barbel (Barbus barbus) or the common roach (Rutilus rutilus), this assumption does not apply to the crucian carp. This may be because the above species are found in lotic (stream) habitats and so most are able to disperse relatively easily. In contrast, the crucian carp have a more limited dispersal potential because they prefer lentic (stagnant) waters, isolated pools and small lakes. This difference in characteristics seems to have limited the ability of the crucian carp to spread in the upper Danube basin (in the Czech Republic, this area is bounded by the Český Les, Šumava, Novohradské hory, Českomoravská vysočina, Kralický sněžník, Oderské vrchy, Jeseníky and Moravskoslezské Beskydy mountains). This area may have acted as a barrier to the spread of the Danube lineage to the north-west (within the Czech Republic into Bohemia, parts of northern Moravia and Silesia).

At present, the results of our analyses show that the mixing of the different lineages (i.e. the northern and the Danube lineages) in some areas or the presence of the Danube lineage in the Elbe basin. This is important information about the structure of the populations in the Czech Republic, which plays an important role in the conservation of the crucian carp and it is necessary to respect the limits of their original distribution when trying to repatriate the species.

Where can I find out more?

Invasive species and competition:

Articles by Ondra Dočkal:

Tapkir, S., Boukal, D., Kalous, L., Bartoň, D., Souza, A.T., Kolar, V., Soukalová, K., Duchet, C., Gottwald, M., Šmejkal, M., 2022. Invasive gibel carp (Carassius gibelio) outperforms threatened native crucian carp (Carassius carassius) in growth rate and effectiveness of resource use: field and experimental evidence. Aquat Conserv 32 (12), 1901-1912.

https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.3894

Tapkir, S., Thomas, K., Kalous, L. et al. 2023. Invasive gibel carp use vacant space and occupy lower trophic niche compared to endangered native crucian carp. Biol Invasions 25, 2917-2928.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-023-03081-9

Šmejkal, M., Thomas, K., Kořen, V., Kubečka, J., 2024. The 50-year history of anglers' record catches of genus Carassius: circumstantial evidence of wiping out the native species by invasive conspecifics. NeoBiota 92: 111-128.

https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.92.121288

Šmejkal, M., Kalous, L., Auwerx, J., Gorule, P. A., Jarić, I., Dočkal, O., Fedorčák, J., Muška, M., Thomas, K., Takács, P., Ferincz, Á., Choleva, L., Lamatsch, D. K., Wanzenböck, J., & Van Wichelen, J., 2025. Wetland fish in peril: A synergy between habitat loss and biological invasions drives the extinction of neglected native fauna. Biological Conservation 302. Elsevier Ltd.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2024.110948

Jeffries, D. L., Lawson-Handley, L., Lamatsch, D. K., Olsén, K. H., Sayer, C. D., & Hänfling, B., 2024. Towards the conservation of the crucian carp in Europe: Prolific hybridization but no evidence for introgression between native and non-native taxa. Molecular Ecology.

https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.17515

Reaction to predators

Brönmark, C., Miner, J.G., 1992. Predator-induced phenotypic change in body morphology in crucian carp. Science (1586) 258, 1348-1350.

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.258.5086.1348

Bronmark, C., Paszkowski, C.A., Tonn, W.M., Hargeby, A., 1995. Predation as a determinant of size structure in populations of crucian carp (Carassius carassius) and tench (Tinca tinca). Text. Ecol Freshw Fish 4, 85-92.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0633.1995.tb00121.x

Domenici, P., Turesson, H., Brodersen, J., Brönmark, C., 2008. Predator-induced morphology enhances escape locomotion in crucian carp. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 275 (1631), 195-201.

https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2007.1088

Hybridisation

Article by Lukáš Kalous about the history of the Carassius fish:

https://ziva.avcr.cz/files/ziva/pdf/karas-stribrity-a-jeho-pribuzni.pdf

Papoušek, I., Vetešník, L., Halačka, K., Lusková, V., Humpl, M., Mendel, J., 2008. Identification of natural hybrids of gibel carp Carassius auratus gibelio (Bloch) and crucian carp Carassius carassius (L.) from lower Dyje River floodplain (Czech Republic). J Fish Biol 72 (5), 1230-1235.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8649.2007.01783.x

Food and ecology of the crucian carp

Holopainen, I.J., Tonn, W.M., Paszkowski, C.A., 1997. Tales of two fish: The dichotomous biology of crucian carp (Carassius carassius (L.)) in northern Europe. Ann Zool Fennici 34 (1), 1-22.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/23735426

Conservation of the crucian carp

Article by Ondra Dočkal:

Zdeněk Suchý's website about the conservation of the crucian carp.

Peter Rolf's website about the conservation of the crucian carp in England:

An interesting book by Peter Rolf - Crock of Gold: Seeking the Crucian Carp, in which he enthusiastically describes his experience of the spread of the crucian carp and their conservation in England. Copp, G.H., Sayer, C.D., 2020. Demonstrating the practical impact of publications in Aquatic Conservation - The case of crucian carp (Carassius carassius) in the East of England. Aquat Conserv 30 (9), 1753-1757.

https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.3353

Thomas, K., Brabec, M., Kalous, L., Gottwald, M., Bartoň, D., Grill, S., Kořen, V.,

Tapkir, S., Šmejkal, M., 2024. Anthropogenic induced drivers of fish assemblages in

small water bodies and conservation implications. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol.